Settlement

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2023-01-20

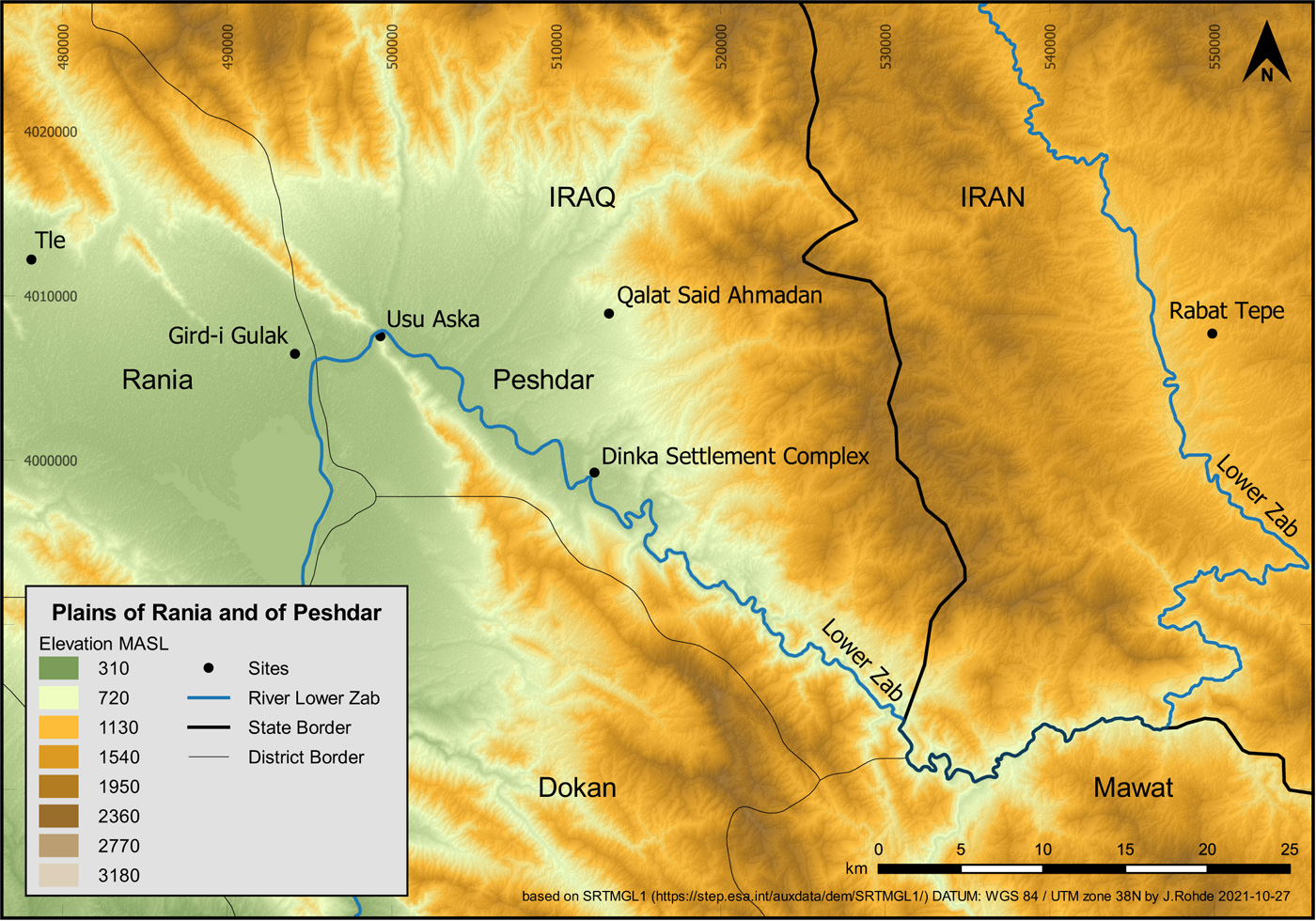

The Dinka Settlement Complex is located in the Sulaymaniyah Province, 5 km south of the modern town of Qaladze (also Qalat Dizeh and Qala Diza) in the Peshdar Plain, which is a narrow, crescent-shaped plain on the upper reaches of the Lower Zab River in the Kurdish Autonomous Region in Iraq. The Peshdar Plain is bordered by the river on one side and steep mountain ranges on the others. To the east, the plain is delimited by the chaîne magistrale of the Zagros Mountains, which corresponds to the present-day border between Iraq and Iran. Its highest peak is the Kuh-e Ibrahim in the Qandil range with an altitude of 3,587 m. To the west, a sequence of lower mountain ranges consisting of Kukh-i Resh, Shakh-i Asos (up to 1,546 m high), and Kurkur Dagh separate the Peshdar Plain from the Rania Plain, with the impressive gorge of Darband-i Rania (also known as Darband-i Sangasur and Darband-i Ramkan) providing a narrow corridor linking the two regions. The Lower Zab has its source in northwestern Iran on the eastern slopes of the Qandil at Piranshar. Running through the Mirabad and Sardasht valleys, the river breaks through the châine magistrale of the Zagros at the southern end of the Peshdar Plain, from whence it runs in a northwesterly direction along the edge of the Peshdar Plain to the pass at Darband-i Rania. There, the course of the river makes a southwesterly turn in the direction of the Rania Plain and passes through the western foothills of the Zagros before eventually reaching the Mesopotamian Plain, joining the Tigris about 30 km south of the city of Assur. Seen from the Mesopotamian lowlands, the various constituent mountain ranges of the Zagros, running from northwest to southeast, are formidable obstacles that serve to protect the Rania and Peshdar plains from western incursions and also make them difficult to control from there. At the same time, the Lower Zab serves as an important communication route that directly connects the Mesopotamian lowlands with present-day western Iran, with regions east of the formidable chaîne magistrale of the Zagros.

Further Reading

Settlement Layout

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-23

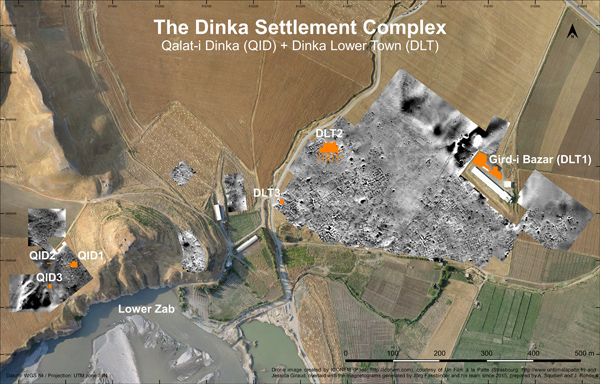

Qalat-i Dinka is an impressive rocky outcrop high above the Lower Zab, the end point of a crescent-shaped hill range that divides the Bora Plain - a subunit of the Peshdar Plain - from the region of Qaladze to the west. Qalat-i Dinka rises up to 40 m above the Bora plain and is relatively flat at the highest point. Erosion has left few archaeological layers or features on the steeply sloped hilltop. The settlement extends across both sides of the ridge. On the western slope of the citadel, relatively high up where the slope becomes flatter, three operations, known as Qalat-i Dinka (QID) Operation 1-3, are located. On the east side of the ridge, situated at the foot of Qalat-i Dinka about 700m to the west in the Bora plain lies the approximately 5 ha flat settlement mound Gird-i Bazar = Dinka Lower Town (DLT) Operation 1, which is part of the extensive lower town. Between Gird-i Bazar and Qalat-i Dinka, the operations DLT-2 and DLT-3 are also located in the Bora Plain.

Between 2015 and 2021, the Peshdar Plain Project has conducted 10 excavation campaigns: three in Gird-i Bazar adjacent to the chicken farm (GiB/DLT1), three on the western slope of Qalat-i Dinka (QiD 1-3), and two each in the lower town between Gird-i Bazar and Qalat-i Dinka, in operations DLT-2 and DLT-3. The results from these six operations spread across different functional settlement areas, in combination with the results of the geophysical surveys, show that the Iron Age settlement consisted of a fortified upper town on the western slope of Qalat-i Dinka, and a large lower town spreading across the Bora Plain at the foot of the eastern slope of Qalat-i Dinka. The area between Gird-i Bazar and Qalat-i Dinka was densely covered with buildings that are separated by streets and alleys. The road system and blocks of buildings are oriented and organized in a semicircle with Qalat-i Dinka as its centre. It has been clearly established that this lower town was not enclosed by a wall – the mountain ranges and the course of the Lower Zab encircling the crescent-shaped Bora Plain seemingly offered enough protection.

Operation area in sqm, Campaigns, and respective publications

| Operations | area in sqm | Campaigns | Publications | Size |

| QID1 | 200 | spring 2016 | 4P2, C | [158MB] |

| spring 2018 | 4P4, D | [124MB] | ||

| autumn 2019 | 4P5, C | [172MB] | ||

| QID2 | 19 | spring 2018 | 4P4, D4 | [124MB] |

| QID3 | 65 | spring 2018 | 4P4, D5 | [124MB] |

| DLT1 | 1153 | autumn 2015 | 4P1, C | [10MB] |

| autumn 2016 | 4P2, D | [158MB] | ||

| autumn 2017 | 4P3, D | [180MB] | ||

| DLT2 | 1013 | spring 2017 | 4P3, C | [180MB] |

| autumn 2021 | see here | |||

| autumn 2022 | see here | |||

| DLT3 | 80 | autumn 2018 | 4P4, E | [124MB] |

| spring 2019 | 4P5, I | [172MB] |

Settlement Phases

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2023-01-20

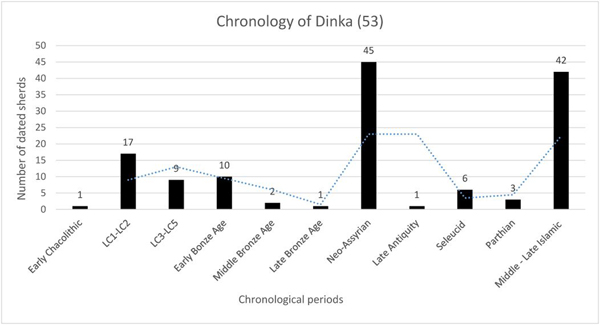

The Dinka settlement complex is a multiperiod site. Between the investigations of the Peshdar Plain Project (PPP) with its geoarchaeological, geophysical and archaeological results, and the archaeological survey of the Mission Archéologique française du Gouvernorat de Soulaimaniah (MAFGS), settlement remains ranging from the late Neolithic to the present have been encountered. The function of the settlement and the size of the settlement varied significantly over time. The Dinka Settlement Complex reached, by far, its largest occupational extent of about ca. 60 ha in the Iron Age.

Further Reading

- 4P1, B3 [10MB]

Halaf Period

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-11

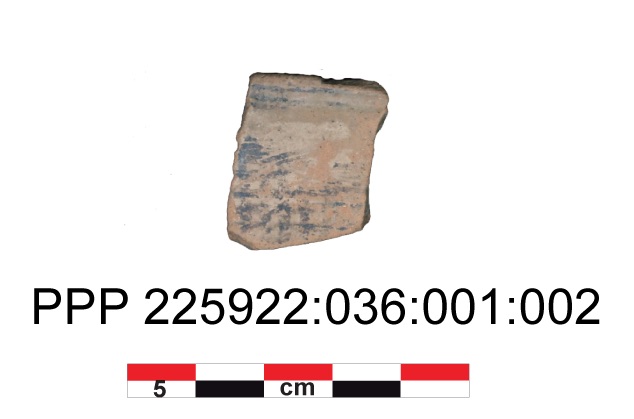

During the fall 2018 campaign, a painted pottery sherd was found in operation DLT-3 in a fill deposited to the south of Building S in Outdoor Area 65 after the end of the Iron Age occupation period. It is a round thinned rim fragment of a thin-walled bowl made of highly levigated fabric with dark painting on its exterior. Three horizontal lines are located immediately below the rim. At some distance below this is a pattern of numerous lines give the impression of cross-hatching, others are painted obliquely. The painted rim sherd was obviously relocated to the place of discovery and could therefore be much older. Comparable pieces, e.g., from Tell Begum in the Sharizor plain, suggest that the fragment could be interpreted as painted Halaf period fine pottery. If this is true, it is the oldest find from the site.

Further Reading

- 4P4_G1.5.2.1 [124MB]

Chalcolithic

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2023-01-20

In Operation DLT-3, remains of a pottery kiln were found in the north-western section of the geoarchaeological trench GA 42 under Iron Age Building R in the fall campaign of 2018. The construction of the building contributed significantly to the destruction of the kiln. [4P4_E4 (124MB)]. The south-eastern section, which was on the opposite side of trench GA 42, contained a walking surface with Chalcolithic pottery lying flat on it. The walking surface was composed of compact mud and was exposed in the fall of 2018 over an area of approximately 1 m². Thirty-two diagnostic and 140 non-diagnostic sherds were recovered from the kiln, from the floor, and from the overlying soil, including chaff-tempered pottery [4P4_G1.5.2.2 (124MB)]. The kiln was further excavated during the spring 2019 campaign [4P5_I (172MB)]. Based on the preserved remains it was reconstructed as a free standing, double-chamber updraught construction, with an underground combustion chamber below and the firing chamber above. In the centre, remains of a free-standing central column with a diameter of about 30 cm about 90 cm high are preserved, which originally supported a perforated kiln floor [Fig._4P5_I2 (172MB)]. However, remains of the upper kiln structure were not preserved in situ; they had fallen into the filling of the combustion chamber. The kiln finds a convincing typological comparison in the ceramic kiln Darre-ye Bolāghi, site 131, as well as the so-called development line V in Arisman in Iran [4P5_I3 (172MB)]. A charcoal sample taken from the backfill of the kiln yielded a 14C dating that places the kiln in the Chalcolithic period (MAMS-41835): 5218 - 5024 cal BC (with 95.4% probability. Calibration software OxCal v.4.3.2). [4P5_I.5 (172MB)]. 24 diagnostic and 83 non-diagnostic sherds were recovered from the kiln in 2019, whose technology, wares, and shapes corresponded very well with those found on the floor on the other side of Geoarchaeological Trench GA42 [4P5_I.4 (172MB)].

Further Reading

Bronze Age

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-30

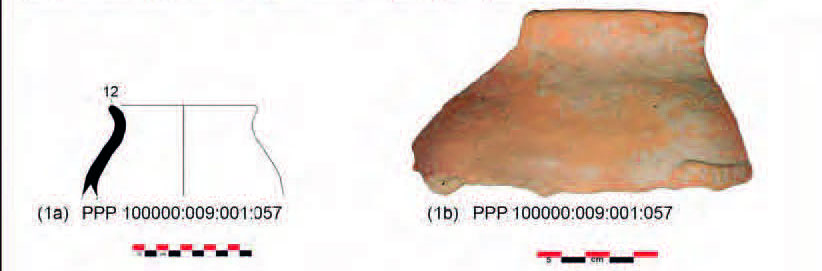

Site surface pottery already indicated that the archaeological site was occupied during the Bronze Age [4P1_B3 (124MB)]. During the 2016 campaign in QID-1, an orange, chaff-tempered rim sherd with an appliqué on its shoulder was found in the the fill of a looting pit. The appliqué possibly represents a scorpion. If this is the case, the piece could be dated to the late third millennium BC based on comparable pieces [4P4_G1.4.1 (124MB)], [Fig. G1.10 (1a), (1b) (124MB)].

Further Reading

- 4P4_G1.4.1 [124MB]; 4P1_B3 [10MB]

Iron Age: Qualat-i Dinka Operation 1

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-29

The ancient occupation on the western slope of Qalat-i Dinka was first investigated in 2016 in a 42 sqm test trench of 42 sqm. In the spring of 2018, operation QID-1 was expanded to 94 sqm, and in the fall of 2019 it was further expanded to approximately 200 sqm. Additionally, the two excavation sites QID-2 and QID-3 were added to record a possible fortification that had been revealed by the geophysical prospection.

The excavations in QID-1 revealed the remains of Building P, a detached structure of impressive size composed of two rooms. The wall bases are much wider (1.60 m) compared to those in the Lower Town. The flooring of room 58 consisted of a pavement formed with burnt clay bricks and flat stone slabs. A charcoal sample from a joint between two bricks yielded a date of 1001-847 calBC, which is consistent with the dates previously preserved in the Lower City. The pottery also suggests a contemporaneous use of the building with the Lower Town. The outdoor area surrounding Building P was constructed with gravel packages that follow the contours of the natural slope of Qalat-i Dinka, sloping from northeast to southwest. Here, the remains of a number of graves were found, which were heavily disturbed by looting. Due to the extensive destruction of the context, it has not been possible to observe a precise stratigraphic sequence. It is therefore unclear whether any graves predate the construction, or date to a time after the building was no longer used, and it is equally impossible to determine whether any of the burials were deposited while Building P was in use. The valuable finds as well as the monumentality of the building indicate that high-ranking personalities acted and were buried at Qalat-i Dinka. Unfortunately, large parts of this excavation site, including the floor, have been so badly disturbed by modern robbery excavations that it is difficult to obtain detailed stratigraphic results.

Further Reading

Iron Age: Qalat-i Dinka Operation 2

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-29

About 40 m west of QID-1, further down the slope, a 10 x 2 m excavation referred to as QID-2 was opened in spring 2018. The remains of a stone construction were exposed, rising up to 2 m in height over a length of 7 m. It was covered with the same pottery encountered elsewhere at Dinka Settlement Complex. We interpret this massive stone structure as a glacis, a commonly used element of military fortifications in ancient times. At the highest point, there is a depression on the glacis. It is possible that a palisade of wooden piles was once embedded there, but it is no longer preserved.

Further Reading

- 4P4, D4 [124MB]

Iron Age: Qala-i Dinka Operation 3

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-29

Opened in the spring of 2018 and located a distance of 40 m from QID2, the trench QID3 revealed the remains of a long wall made of loosely assembled stones, employing a building technique that markedly differs from that used for the walls of all buildings hitherto excavated at the Dinka Settlement Complex. The stones of this construction were embedded in dark brown soil, onto which walking surfaces of the adjoining outer areas abutted. We interpret this feature as an earthen rampart, on which a palisade may have originally provided protection for the upper town.

Further Reading

- 4P4, D5 [124MB]

Iron Age: Dinka Lower Town 1 = Gird-i Bazar

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-29

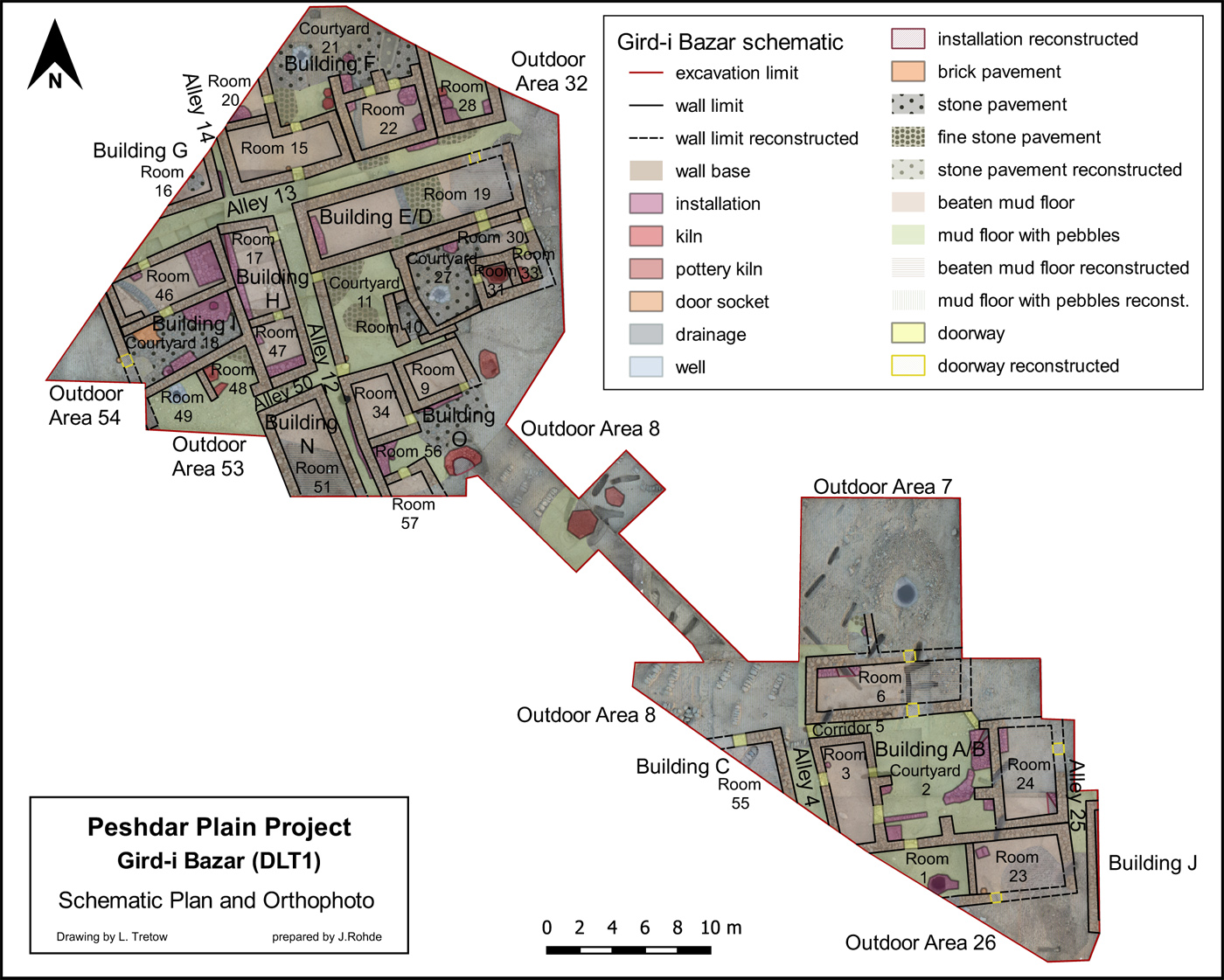

From 2015-2017, rescue excavations were carried out on the shallow mound of Gird-i Bazar after it had been severely damaged by the construction of a chicken farm and its enclosure with a metal fence. Here, by exposing an area of about 1150 sqm, a clear picture of the organization, nature, and function of this settlement area, containing at least 11 buildings, was obtained. The buildings were founded on the bedrock. The floors of the rooms, courtyards, and alleys are connected by doors and passages. Structural changes can be observed only in some places, so it can be assumed that the buildings were inhabited for one main occupation period, which can be further divided into subphases in the areas where changes were observed. To the west of this area, six buildings were unearthed, separated by and accessible from narrow alleys. Of these, two were completely excavated: Building F/D covers about 150 sqm and Building H/I about 120 sqm. The discovery of three ceramic kilns, the pivot stone of a slowly rotating potter's wheel, and other items connected to pottery production indicate the existence of ceramic workshops in this part of the Dinka Settlement Complex. The houses at Gird-i Bazar were also homes, as they feature the essential installations needed for everyday life such as wells for accessing fresh water, drains that carried wastewater into the alleys, and bread ovens. To the east of these houses lies a large open space, and beyond it are additional buildings that followed a similar layout, of which Building A, covering an area of about 150 sqm, was most extensively excavated.

Further Reading

- 4P1, C [10MB]; 4P2, D [158MB]; 4P3, D [180MB]

- Squitieri, Herr, Amicone 2022, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 67: 101443

Iron Age: Dinka Lower Town Operation 2

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2023-11-22

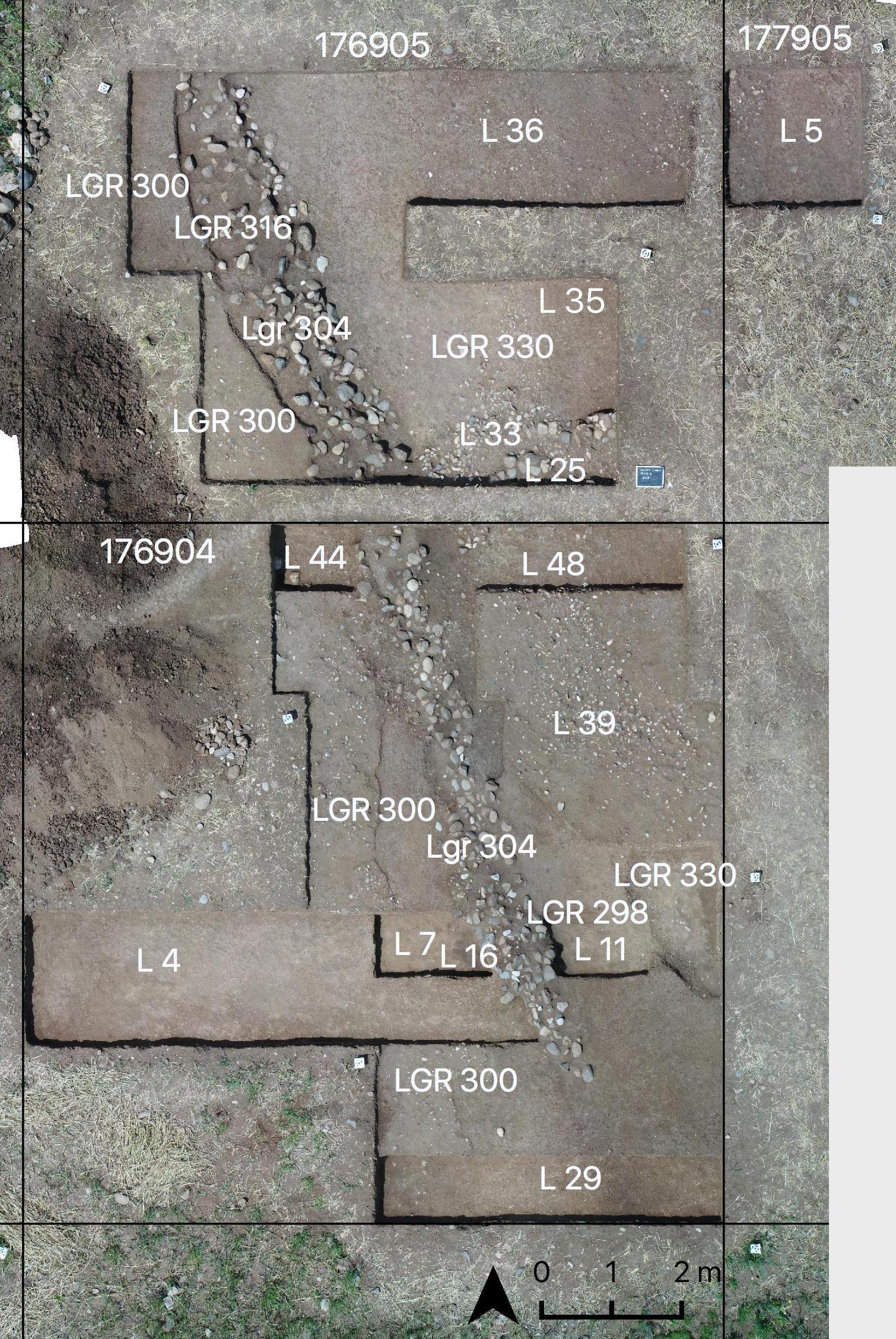

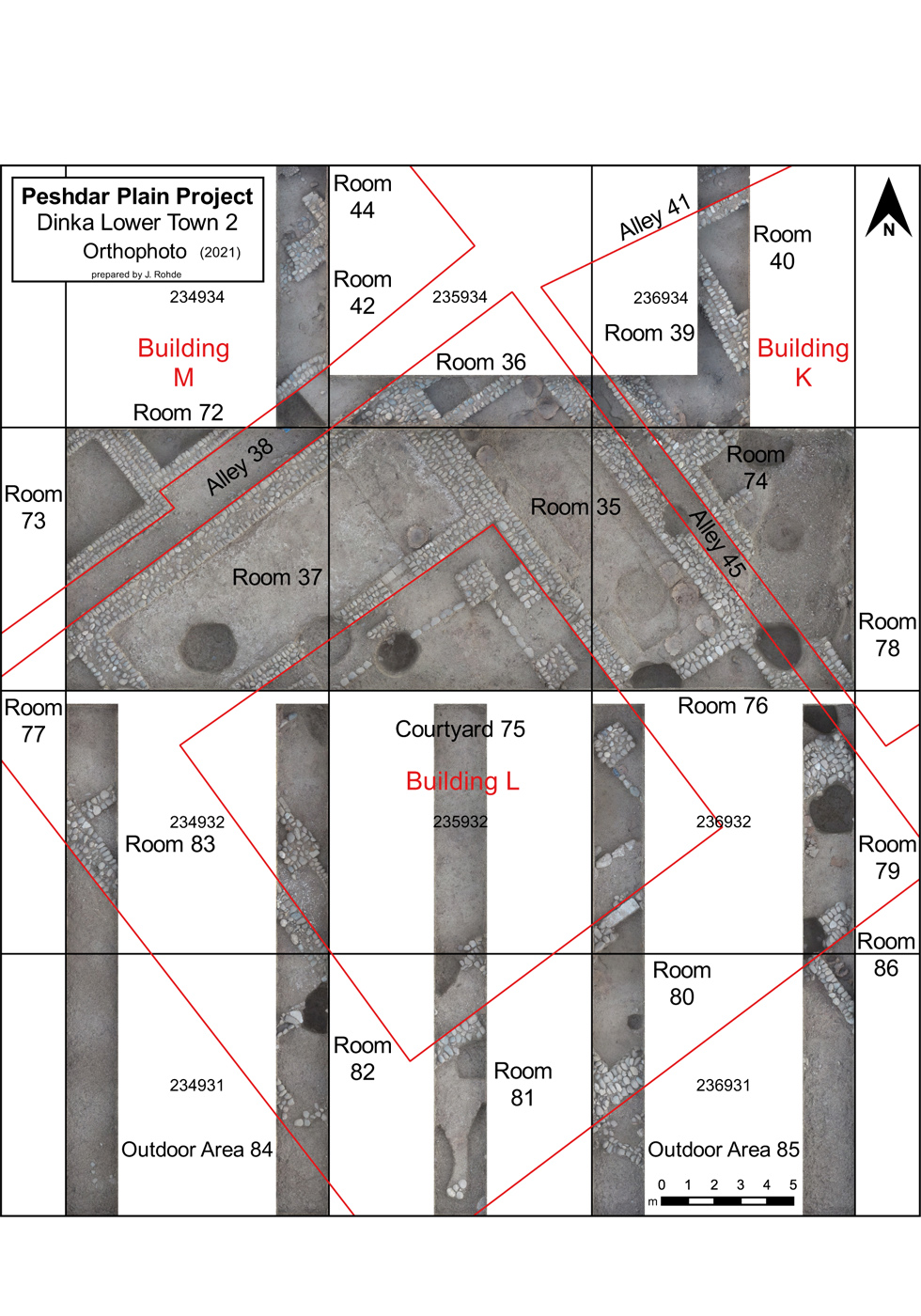

Operation DLT-2 is situated in the lower town in an elevated position spatially distanced from the rest of the settlement. A complex of three larger buildings had been observed in the 2016 magnetogram. In spring 2017, a first test trench of 68 sqm was excavated in this area, which was dubbed DLT2. The results confirmed that building features exposed by excavation matched those observed in the magnetogram and further indicated that well-preserved building remains could be expected only 20-25 cm below the modern surface, i.e. directly below the ploughing zone. The magnetogram revealed that the extent of Buildings K (ca. 330 sqm), L (ca. 700 sqm), and M (ca. 530 sqm) was significantly larger than other recognisable architectural units in the lower town. Already their position and their size therefore suggested the importance of this complex within the settlement. This hypothesis was supported by the results of the initial excavations in spring 2017. Room 35 in the largest Building L is a storage room and contains very large storage vessels arranged along the long sides of the room. Two charred seeds of emmer (triticum dicoccum) from the bottom of one of these vessels, from the northern corner of the room, yielded radiocarbon date ranges of 1012–894 calBC and 930–824 calBC, which match the majority of radiocarbon dates available for Gird-i Bazar and Qalat-i Dinka. This indicates that the buildings in these three different areas of the settlement, both within the hilltop fortification and the lower town, were in use simultaneously. This is also supported by the ceramic inventories recovered from the floors of the DLT2 buildings, which match the pottery found in Gird-i Bazar in terms of ware, form, and production technique, according to macroscopic and petrographic analyses.

In the 2021 autumn campaign, an area of 495 m² was opened to investigate Building L and its adjoining areas. The 2022 autumn campaign was dedicated to Building K and the 2023 autumn campaign to Building M. In each case, excavations were carried out on an area of 450 m² to investigate selected areas of the buildings and associated adjacent structures. Preliminary results can be found here.

Further Reading

- 4P3, C [180MB]

Iron Age: Dinka Lower Town Operation 3

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-28

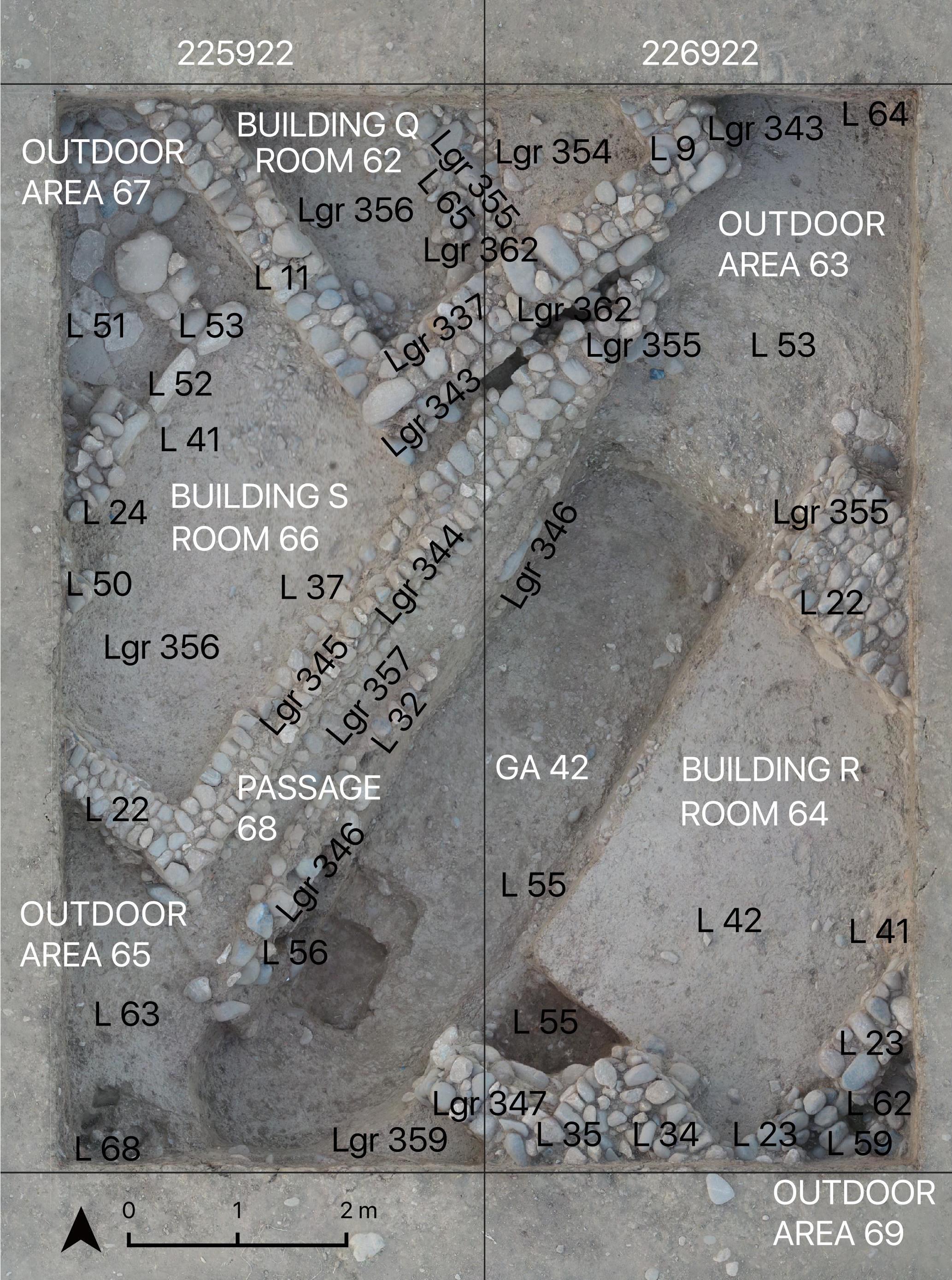

In autumn of 2018, an area of 80 sqm was excavated at DLT-3 that brought to light buildings and rooms with small-scale stone architecture and a pottery inventory that closely matched what was already known from Gird-i Bazar. However, unlike in Gird-i Bazar, two successive construction phases could be observed in Buildings Q and S, as a section of Building Q had been partly covered by Building S, which was built in the more recent construction phase. Presumably, this reflected changing spatial requirements. The adjoining Building R, on the other hand, remained unchanged and was in continuous use throughout the same period.

Further Reading

- 4P4, E [124MB]

Hellenistic-Parthian-Sasanian

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-28

The disturbed Grave 98 in QID1 was excavated above the stone wall of Room 58. The stratigraphic position of these bones already indicated a dating to a period after the end of use of the building and after the Iron Age, and the 14C analysis indeed revealed a radiocarbon date range from 355–93 calBC (95.4 % probability). However, it is currently impossible to state whether this individual lived in the late Persian period, in the Seleucid era, or in the early Parthian period. [4P4, D3.2.1 (124MB)]

After the Iron Age Main Occupation Period and a hiatus, the shallow mound of Gird-i Bazar was used as a burial ground in the Sasanian period. 92 graves were identified, which had been inserted into the Iron Age features from a newly created and higher ground site surface. 62 graves were excavated, from which a total of 71 individuals' skeletal remains were recovered. A radiocarbon date revealed from a tooth in grave 45 yielded the date 389-535 calBC. [4P3, H (180MB)]

Further Reading

- [Squitieri, Andrea. "The Sasanian Cemetery of Gird-i Bazar in the Peshdar Plain (Iraqi Kurdistan)." Iran 60.1 (2022): 73-90;

- Sasanian pottery has been found in the upper fill and the topsoil in operation DLT-3 [4P4, G1.5.2.3 (124MB)] and in the geoarchaeological trench GA44 [4P4, G1.6 (124MB)].

Islamic period

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-28

Surface ceramic finds indicate that the site was also used in the Middle Islamic period. [4P1, B3 (10MB)]. Four clearly assignable sherds of glazed pottery have been found in the topsoil, looting pits, and later fills in Qalat-i Dinka [4P4, G1.4.2 (124MB)]. However, no architectural remains associated with this period have been brought to light so far.

Modern

Author: Janoscha Kreppner | last update: 2022-11-28

The Modern Occupation Period refers to the recent activities that took place at Gird-i Bazar during the 20ᵗʰ and 21ˢᵗ centuries AD. Modern Occupation period finds include a stone surface, stone installations, and pits dated by the presence of coins to the Saddam era, as well as some cuts and pits caused by the more recent construction of a chicken farm in 2014.

Currently, agriculture is practiced on the western slope of Qalat-i Dinka. At Gird-i Bazar there is a fenced chicken farm with a house. The area of the lower town of the former Dinka settlement complex is used for agriculture. At the foot of Qalat-i Dinka there is a residential house with outbuildings, and to its east and next to the road crossing there are modern graves.

.jpg)

.jpg)